A few years ago I wrote about RPGMaker horror Games for The Arcade Review. What interested me about them was their built-in limitations from the RPGMaker platform that didn’t really make much sense on a basic level as something to try and make a horror game with. For the most part you were limited to a specific range of visual effects, actions, and user interface options, none of which looked like the survival horror tropes of the day, and to make things even more challenging you had to condense the ability to create atmosphere and disturbing imagery into fairly basic sprite-based imagery. In the time since I’ve written that essay, pixel horror has become a bit of a phenomenon. There’s recently been a lot of buzz around Faith, a pixel horror title styled around the even more limited pallette and capabilities of early home computers like the ZX Spectrum, and games referencing or in tribute to Yume Nikki’s minimal gameplay and visual style still come out regularly through its 10-year anniversary.

I mostly credit games made in RPGMaker, like Yume Nikki and Ao Oni as the main influences in pixel horror becoming a defined and viable genre, and as further evidence the number of spinoffs and fangames they’ve produced that have often become significant projects on their own. These games mostly spread through fan communities and message boards, as a part of other forms of production in response to games, theorycrafting, fanart, building walkthroughs and wikis, and so on. Something that also spreads through similar channels and I think, takes advantage of this existing horror aesthetic, are various video game themed “creepypastas.”

This weird article about online mattress sales was making the rounds the day I started working on this piece. What’s weird about it is not really the content or the events it describes; rumors or even evidence of review video YouTubers being bribed and/or bullied by their commercial affiliates are something I’ve also seen in the Makeup Artist sections of YouTube, and even the emergent area of slime videos. The way this familiar story, of pressure from companies impinging on the independence of reviewers in both carrot and stick ways becomes ridiculously compelling in how it is written, though. Sensible everyman who can’t say no to a convenient, free, brand-new mattress is sucked into a mysterious network of mattress sellers and reviewers and gradually a sinister air begins to seep in, leading up to a climactic reveal that totally changes the tone of the initial encounter.

It’s really good journalism, because I can’t imagine most of us would have read much about online mattress review related litigation if it was written any other way. But the way it was so compelling, such a weirdly compulsive read (I had just decided to go to bed in five minutes when I saw the link and ended up staying up for another hour to read the whole thing and post about my disbelief), reminded me of something else. The set up, the banal subject matter, the twist, the entire tone and structure… this was a creepypasta about mattresses, essentially. Maybe it was a kind of absurd 1:30 AM kind of conclusion, but it also provokes questions about what makes a creepypasta a distinct form of writing, their influence, and what they represent.

Creepypasta are essentially the evolution of the ghost story and urban legend in online space. Ghost stories and urban legends were primarily transmitted orally for most of their history, though they’d occasionally be collected into books. In this case though, with only a few exceptions (maybe The Girl With The Green Ribbon is a good illustrative example) do illustrations or photos emerge as emblematic of the story.¹

The textual cadence of early chain emails, which occasionally went into supernatural or spooky territory mirrored the repetition and long ledes of these ritually repeated and shared stories. As the internet progressed and proliferated, the ability to attach photos to these stories that were passed around also shaped what was transmitted in this way. The “9/11 Tourist Guy” hoax emails originated as a joke image distributed to a few friends, a few minutes in Photoshop blowing up into controversy and attention its originator never sought. This was fairly early on in the lifetime of accessible and convincing image editing capabilities on personal computers, and people were likewise much more likely to be legitimately duped by a simple Photoshop job.

Now, with the proliferation of image editing, down to filters and beauty apps that can be applied with a tap, more then ever there is a kind of built in assumption that all digital images are fabricated to an extent. Our decreased trust in images also probably explains why there are several important differences in how creepypasta operates and is disseminated as opposed to urban legends and hoax chain emails. The Godzilla NES creepypasta by Cosbydaf is a particularly good example of this and also unusual in its scale and sophistication.

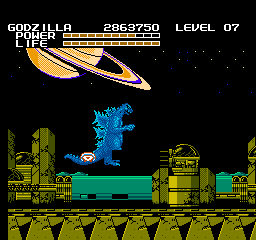

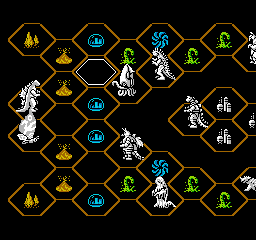

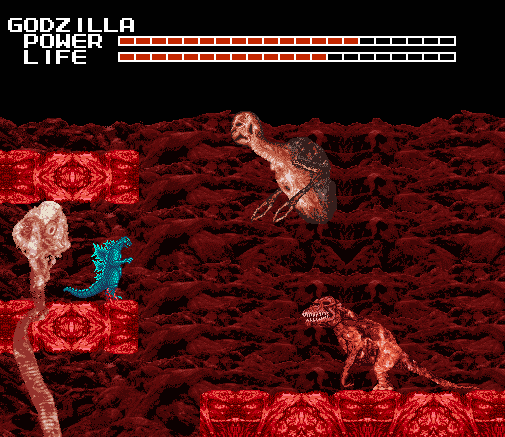

Godzilla: Monster Of Monsters was released for the NES in 1989. Despite its age, the game does a surprisingly good job of depicting Toho’s iconic kaiju in impressive detail. The music is also considered above average for the NES catalog, but the gameplay, moving Godzilla or Mothra around on a gameboard-like overworld, plodding through a long level of smashing things as your chosen monster with each move and then entering equally drawn out boss fights if you run into one of the other monster “pieces” moving around the “board.” Repeat this for a 8 planets from Earth to Planet X and it becomes apparent that the game has a very modular and repetitive structure that may quickly become tiresome for some people. This might be its main weakness that keeps it a fairly obscure entry in the NES library, but it also relies on specialist knowledge and interests which are also pretty obscure in the English-speaking world.

Everyone knows Godzilla, for the most part. The original film is considered a classic and the Hollywood-helmed sequels and remakes are popular enough but most people who see those films outside of Japan don’t know much about the film company Toho or it’s long library of tokusatsu films, media that relies on the spectacle of both practical and CGI special effects. Elaborate costumes and sets, staged explosions and smoke bombs, stunt action sequences and so on typically support science fiction storylines, and also generate a big market for toys and other products with distinct characters like Kamen Rider, Ultraman, or, of course, kaiju like Godzilla and Mothra. It’s a distinct style of production that is occasionally exported (see the Power Rangers for another example), but has yet to gain an equivalent foothold in another country.² So, many of the boss monsters, the graphical centerpieces and narrative climaxes of a videogame based on Godzilla and related monsters, aren’t nearly as familiar or impactful to audiences outside of Japan unless they have an unusual familiarity with a foreign film genre.

The game is slow and repeats the same modular structure with a gradual ramping up of difficulty, and mostly deals with characters that would be obscure or inscrutable to an English-speaking audience. This may seem like a poor choice of subject for a horror story to begin with, where’s the action, where’s the climax, and who even knows what these creatures are to begin with, but the NES Godzilla game was apparently an excellent starting point for developing an elaborate and effective creepypasta.

While there are creepypasta that are not about videogames, and are instead based around mysterious internet sites, crypids, ghosts, or demonic phenomena, the term has almost become synonymous with some sort of videogame-based horror because of the sheer amount of them. The posting of a creepypasta usually takes place on a forum, where it can be told in brief or long installments as posts in a single thread. This gives a sense of real time, the player relays their progress to the online audience and then steps away to play some more. This also allows for feedback during the process that things like chain emails didn’t allow. They couldn’t be changed to be more convincing as people read and decided whether they were spooked enough to forward them or not, but could only be iterated on as writers saw which themes got the most traction.³

Chain mail hoaxes and urban legends tend to prey on the easily duped, and therefore structure themselves to be especially persuasive (or even too horrifying to fully investigate, existing only ever as a warning) to ensure their spread, but the creepypasta audience is one that wants to be duped. There’s an existing knowledge that this is an elaborate fake, but in that context how real is it? It becomes a chance to demonstrate both obsessive, in-depth knowledge of a game, a key point of gamer culture, and knowledge of the technical aspects of the games to adequately generate convincing images of the phenomena effecting the game, all in addition to the ability to tell a compelling and creepy story more generally.

The Godzilla NES creepypasta starts out in a very standard way for the genre. Perhaps because of their physical hardware, prone to the decay, loss, and interference that purely digital files aren’t as subject to, original or bootleg copies of older games, come by in mysterious circumstances, are a typical starting point of creepypasta. The rediscovery of these games, which the protagonist usually has previous experience with, is seen as a harmless and happy occasion because of the nostalgic feelings associated with old videogames. In this case, after parting with his original copy of Godzilla: Monster of Monsters as a kid through a regretted trade-in, he receives a copy from a friend after seeking to recreate his childhood NES game collection. The Godzilla game is the first priority, because of his particular, and perhaps unique love of Godzilla movies in general as well. His playing of the game starts out normally, squaring with his nostalgic memories, though seeming a bit more basic and repetitive than the rose-colored recollection. When the graphics glitch up a bit, he just blows some dust off the cartridge (a common if dubious way to clean troublesome games), restarts and completes the first level of the game without issue.

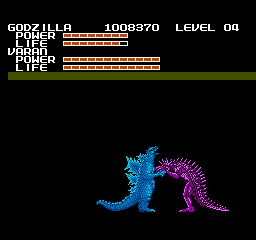

This initial image of nostalgic enjoyment with only a few easily navigated hitches that only enhance the engagement with the lost material dimension of older gaming consoles is important. As the protagonist says, he sought out this experience because it was from a time when things seemed safer, routine. The reason that the subject of a creepypasta is often an older game that is being replayed is also because it offers a diversion from the routine. Soon after the initial glitch something undeniably novel appears, a boss monster which was never a part of the original game. The protagonist excitedly hopes that this indicates that their version is somehow special, a prototype or a ROM hacked edition maybe, but for the target creepypasta audience this is a knowing indication that there’s something meaningfully off about the Godzilla NES cartridge already. The mild graphical errors continue, becoming more unsettling and ominous in the way that they violate the sprites of the monsters, the expected response of the machine to the player’s button-presses. There is a moment of relief when the fight with the new, unexpected monster goes fairly normally, but the player is quickly whisked off the predictable series of planets afterwards, to a stage simply titled “Pathos.”

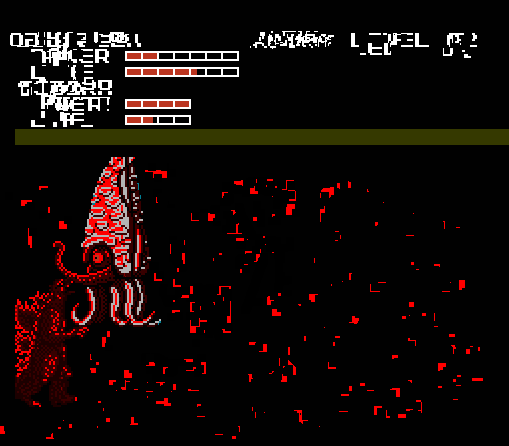

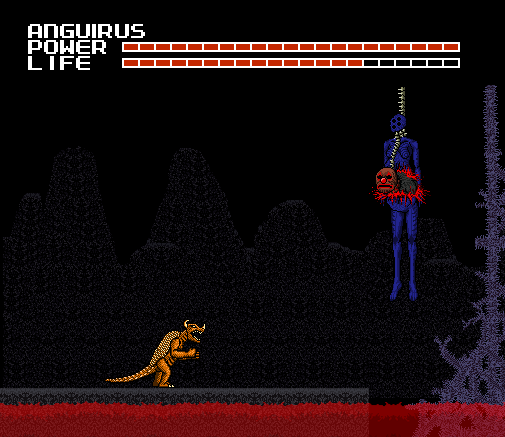

From this point, rather than encountering new levels and monsters with excitement, the protagonist instead admits he could no longer rationalize the abnormalities of his copy of the game. Glitched graphics are no longer explainable as unpredictable malfunctions, but instead “look far too intentional.” The seed of intentionality within glitches, from an unknown source seeping into empty spaces where there should be only random noise, is the crack through which many tech-horror stories enter the real world, from the psychic imprint on the VHS tape in The Ring to the corrupted cassette tapes through which the house speaks in ANATOMY. Once the intentionality becomes impossible to ignore the source of the horror has made its foothold. There is some force at work here, and, at the end of this level he is possibly introduced in the form of a red “spider beast” that appears in a seemingly empty level, stripped of points and health bars where the player is only given the instruction to “run.” Red, as he ends up being called, is the point where the game itself begins to seem sentient and malicious, later seeming to look directly at the player or even torment him outside of the game.

Horror can take the shape of an unwelcome presence but also an inexplicable absence, and as the protagonist’s retelling of his playthrough progresses to this level that was entirely constructed by the mysterious force that altered the Godzilla cartridge, absence also begins to play a role. Stages drained of enemies are eerily unnatural, the music becomes tuneless or doesn’t play at all, and Red’s appearances are usually presaged by these sort of effects.

Intentionality is also attributed to the game through “quiz” sections that ask the protagonist alternately creepy and nonsensical questions, responding with preset expressions that look like an inexplicable pain scale. It gives the game itself an apparent attitude of capriciousness, and reinforces the risk of angering it. It not only taunts with its awareness of the external player, but also interferes with the presupposed freedoms of the gameplay at points, forcing the player to play as Mothra rather than Godzilla at whim.

As the protagonist plays on through levels that repeat in much the same fashion, with impossible creatures that were not included in the original game appearing as bosses, and impossibly complex or realistic graphics and sounds glitching into existence, the creepypasta begins to develop a predictable rhythm. Each stage presents weirder creatures, more unexpected sights, and a curveball moment from the quiz or from the alien creature Red. In an interview, Cosbydaf says he “discovered that it’s profoundly challenging to keep a story where you follow a video game interesting.” Because videogames in general and Godzilla NES specifically are often based on repeating modular parts, it’s easy for a description of the parts to become boring. Without the horror twists, the Godzilla NES creepypasta shows its roots in other forms of player documentation of gameplay, like walkthrough guides and let’s play videos.

The interspersion of obscure Godzilla factoids, appreciation of references to the films and other games, and detailed descriptions of how best to defeat certain enemies often seems to break with the increasingly tense and bizarre horror themes. The player truly can’t be keeping a calm enough head to appreciate that in the moment, right? But they square with the form of friendly expertise typical to these types of gaming documents and their incorporation with more universal horror elements places the Godzilla NES creepypasta and others in an approach to horror that is distinct to videogame communities. The friendly expert persona of these players also creates more stake in what is an inherently repetitive narrative, assigning emotions and motivations to recombined button presses and identical enemy sprites.

The player’s slightly-spooky middle school girlfriend, Melissa, is introduced just past the halfway point of the narrative, during the 6th planet, and is written off just as quickly. Her name appears onscreen for a moment, sparking memory of her in the player and also that he watched her die in a traumatizing truck accident. This seems an unusually grim detail to suddenly add to the story of a guy who simply enjoyed Godzilla movies and NES games as his primary character traits, and falls in line with the unfortunate trend in both videogames and horror more broadly to introduce a female love interest only for her to die horribly to provide character motivation for a male protagonist. However, it also establishes an external contrast to the generally masculine world of monster movies and videogames. Melissa is a counterpoint to the world of brutal violence and unnerving monsters the player seems trapped in, as well as the male sphere of fanboy expertise and retrogaming childhood nostalgia which drew him towards it.

More externalities seep in as the game becomes more and more ominous, flesh and blood and gruesome maternity as a later boss erupts from what appears to be a pregnant, hanging body. The player describes these final sequences as pushing the capabilities of the NES to its limit, but clearly they are beyond anything that was possible with the console. While the visual experience of playing NES games on a CRT screen was different, the number of people for whom early sprite art has been primarily experienced through emulation now probably outnumber the number of people who experienced it on an old television set. This version of pixel art in general has been reclaimed by retro gamers and artgame makers alike for its iconic shapes, clean lines and implicit visual purity, making the eventual gory collage of Godzilla NES creepypasta images especially surprising and unsettling.

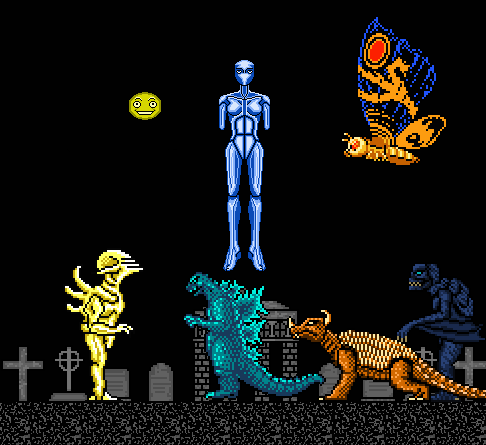

The creepypasta concludes with a climactic battle against Red, who has crossed the threshold of simply being aware of the player (who should be invisible to the game-world, only interfacing with it through his monster avatars), gaining the ability to physically cause him pain when his attacks hit in the game. Like so many RPG final bosses, Red takes multiple forms and requires intervention from an outside force, the spirit of Melissa, represented in the game as an angelic blue figure, to unlock the power to finally vanquish it. Then, all the player-character monsters are restored and reunited, with a final message from Melissa saying they will be together with the player again someday. It’s an unusually positive catharsis for the creepypasta genre, maybe a bit cliche, but regardless the engaging long-telling of the tale still makes it sweet.

Some people argue that taking something apart in an in depth analysis like this ruins its effect, or kills the ability to enjoy it. This wasn’t my goal, nor do I think that necessarily happens when deconstructing creepypasta to have a look at their parts. It’s obvious that the receptive community for creepypasta as well as amateur horror games and fangames are aware of these parts and also enjoy looking at them critically themselves. Comments early on in the original thread where the story of this fateful Godzilla NES playthrough was relayed level by level stated knowing admiration at how good the new sprites looked, how elaborate the edits were, but also teasing critique stating that it would be quite complicated to take this many screenshots from an actual NES console, advice for the writer to more effectively capitalize on their suspension of disbelief. Creepypasta, RPGMaker horror and other horror fangames are based on an interesting premise of navigating towards effective and compelling horror communally, rather than the independent, auteurist approaches to horror apparent in how we talk about the work of Poe or Hitchcock. And naturally, they take horror in new directions specifically suited for online communities and audiences.

In closing, I think the Godzilla: Monster of Monsters creepypasta reveals three particularly important points about creepypasta in general:

1: nostalgia — Many forms of horror deal with the corruption of an idealized, innocent state. That so many creepypasta are about older games represents a nostalgic feeling for the assumed simplicity and purity of these titles. This represents a generational shift in horror topics, and also creates an accessible stage for aspiring game makers and sprite artists to play with early visual styles in videogames.

2: process — A deep awareness of and interest in the process of playing a videogame in itself is what gives these stories their pacing and structure. While they are obviously informed by horror themes and tropes that predate creepypasta or videogames, these themes are filtered through how gameplay is turned into narrative by players, through documents like walkthrough guides, let’s plays, or even how they simply discuss gaming with friends.

3: technology — The material qualities and limitations of technology are fertile ground for new tendencies in horror. Beyond the unnerving ambiguity of static and distortion, playing with popular knowledge of videogames and specific consoles, their technical limitations, repetitive structures and so on, will probably persist as important new elements of horror going forward.

[1] — I also feel like the photo documentation of ghosts, UFOs and cryptids serves a different purpose not strictly related to rumor or fiction in the way urban legends and campfire stories are.

[2] — Similarly, when the properties are used by Hollywood cinema, the awkward but grounded special effects often lose their essence when translated to the otherworldly slickness of “cutting edge” CGI. The immature form of Godzilla in the film Shin Godzilla can look positively goofy, but there’s a weight to the way it stumbles and flops around vs. the slick way Godzilla in the 2014 film swims and dives through the water that makes it uniquely uncanny as well, meshing with how much more real the threat of toxic waste and nuclear radiation have been in Japan’s history.

[3] — This process also exists in creepypasta, and writers can receive blowback as certain previously effective plot elements and structures become predictable and boring in their repetition, but the fact that they are also posted in part on forums for public critique puts the audience in a unique position.