Posted by: Emilie | JUN-11-2019

There are multiple ways of approaching, describing, and analyzing what videogames “do,” but by far the dominant paradigm is to put them in a sort of direct lineage with traditional games that have fairly codified sets of rules like chess. The remit of the field of “game studies” as constructed by institutional maneuvering implies this connection. But increasingly, scholarship taking a view on videogames as made and experienced, rather than as abstracted systems, sets of rules, or universal qualities, has been complicating this comparison. Brendan Keogh, for example, writes in a recent article:

“The videogame, then, can be fruitfully understood as not just a digital game but as an audiovisual-haptic medium, where what is done with the hands, what is looked at on the screen and what is heard from the speakers, in concert, constitute the embodied expressions that the videogame provides. This is not to suggest that nondigital games cannot provide meaningful aesthetic experiences through visual, aural or touch feedback, but that videogame experience is fundamentally constituted from the embodied perception of digital sights and sounds, and tactile hardware.”

Perhaps the reason game studies and games criticism has generally floundered around a discussion of aesthetics (compared to discussions of other forms of visual media), is that, for the most part, the sensory aspects of the videogame are treated as if they don’t matter inasmuch as they are subservient to the system (properly indicating goals and guiding the player) or the narrative (the focus on the “representativeness” of characters and storylines). Aesthetics can be an impressive technological wrapper for the “gameplay” that matters, or a prompt to receive the game and its narrative or themes as either self-reflexive (in the case of pixel art) or generally slightly artsy-different. But how often do we talk about how they -really- look, and what they do visually, beyond them being sometimes “beautiful?”

Full disclosure, of course. Stephen is someone I have written closely with almost since starting writing about games, and during the course of 10 Beautiful Postcard’s development he was someone I spent an increasing amount of IRL time with. The titular postcards in the game are my art and writing, and were also a way to salvage something positive from real-life instances of distance. In short, it’s all very romantic, UGH!!

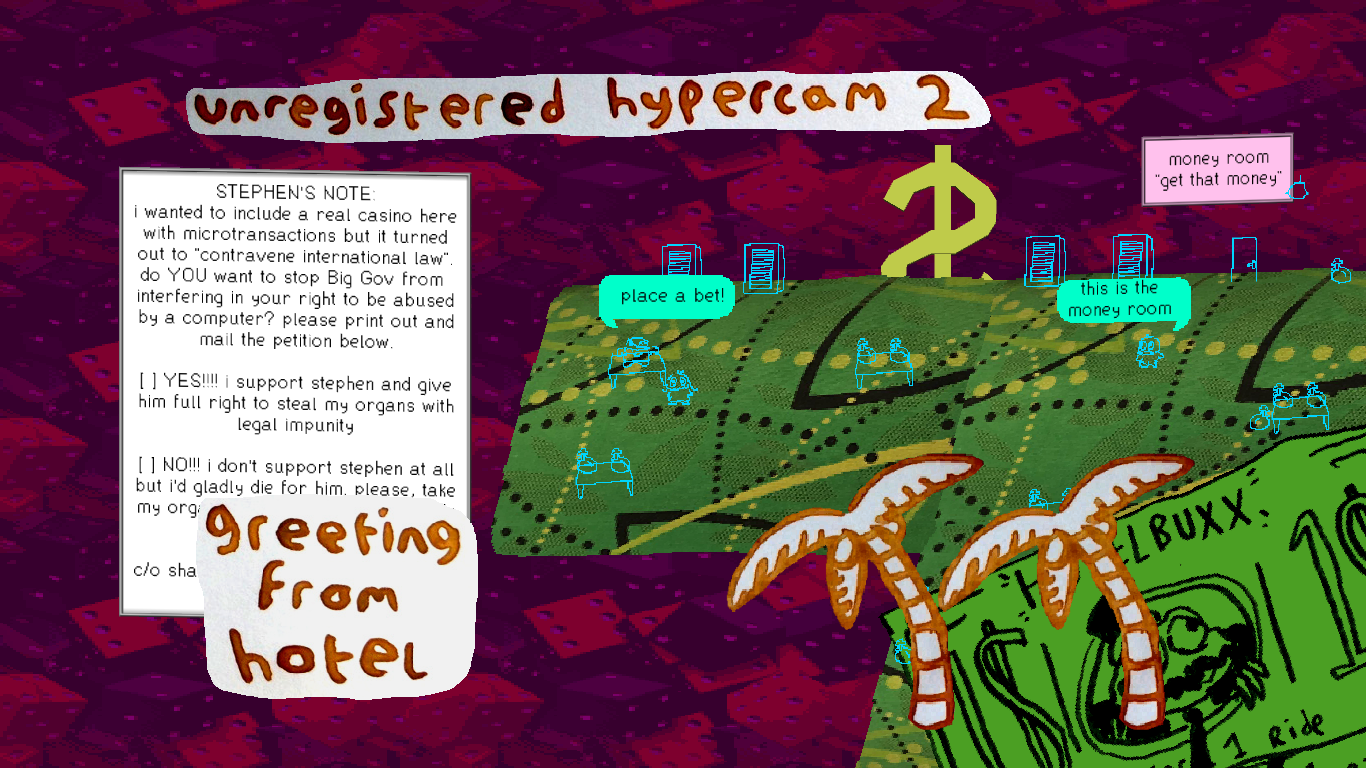

A postcard is a way of conveying spatial experience over distance; “wish you were here.” When I had to travel, I would usually find the most suitable postcards in the teetering wire racks which occur regularly along the roads in a city that get the most foot traffic. These are the cheap, five or six for a euro/pound/dollar ones whose aesthetic leans into the same genericized clip arty sheen and corny overenthusiasm of the 90s “multimedia” boom. Others I would find digging in the boxes at a local Oxfam, anonymous places. They’re all a bit funny, because even when I buy them in the location they’re representing, my relationship to the place the postcard represents is cursory at best, the most hilarious example being the postcard from Melbourne showing bits of city skyline crassly photoshopped against an outback sunset… I spent that entire trip between a university conference center and the cheapest hostel I could get.

My process with making each of the postcards was to mash together the abstracted postcard representation of a real space with a similar abstraction of some sort of mood or internal space. In the zine Space People, Stephen instructs the reader to hold the zine at a 90 degree angle at one point, with one page on the surface in front of you and the other propped up like a backdrop, and the flat surfaces of the zine recede and become a space for little guys to walk around in. I tried to treat the postcards as if they were dioramas I could peer into, or carpets I could walk on. The idea of space inside the screen and exploring that space for its visual novelty alone has long been my primary motivation/fascination with videogames.

I feel that, of the many threads I could pull out, 10 Beautiful Postcards is trying to do two things that are most compelling to me. First of all, it’s pulling at why the institution of “videogames” is how it is due to both the pressures and values of capitalism. Videogames are a primary way that people have become more acclimated to computers and technology entering their lives more and more intimately. Early on it was a technology that existed with no particular reason or expectation (albeit in the context of the military industrial complex) but had enormous amounts of speculative capital coming its way soon as the “next big thing.” And the concept of “value” itself implies expectations.

While history from that point on is often told in a timeline of advancing mainstream console “generations” and defining “classics,” the history of videogames is just as much a series of bizarre attempts (adaptations of any analog activity you could imagine, girl games, multimedia CD-ROM, playful “software tools” and so on) to find what people want to “do” with computers. Now, as the insane sums of money put into the industry collect at the top, increasingly indistinguishable console catalogues become more conservative in their offerings, reiterating old IP and rereleases, and in the “independent” and mobile spaces experimentation is all too often pushed to the margins in favor of retro tributes or whatever can serve as a lootbox vehicle. What a videogame is, and more broadly what people do on their computers has been narrowed and circumscribed.

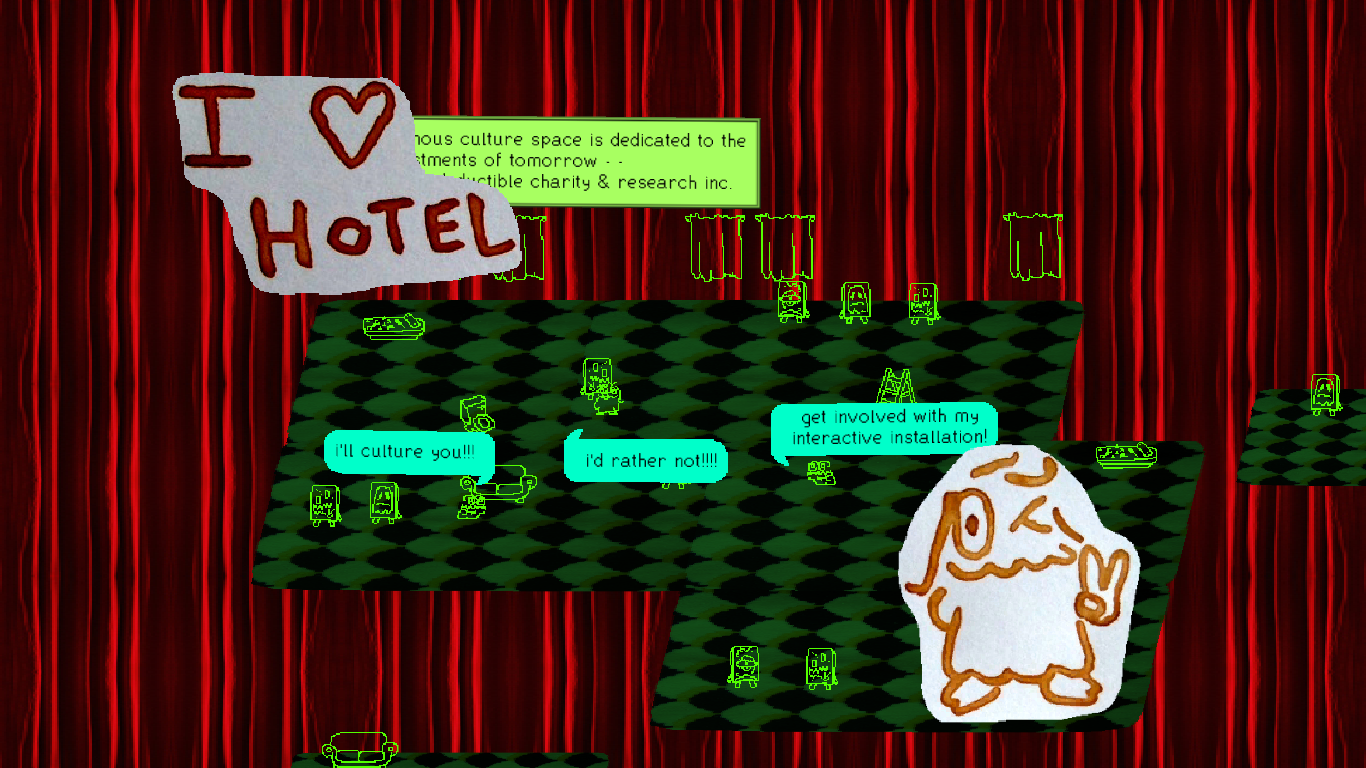

Meanwhile, the freedom of the “gig” economy, within which a lot of scrounging workers relax with videogames between gamified ridesharing, call center work, or endlessly chasing up freelance payments, has in reality manifested less choice with more hassle, benefitting only the braindead CEOs who collect billions without a shadow on their conscience for reinventing “a bus” or hype up the brilliance of their studio’s latest Dead Wife Game. This is the context in which most of 10 Beautiful Postcards takes place. The hotels, which both Mr Hotel and Mr Hostel are trying to franchise out and extend indefinitely, all contain doors leading to shadowy financial flows, questionable stores of value and increasingly abstracted get rich schemes. It’s a lot like the tech industry in general, except it’s a hotel.

Videogames have leaned into this logic of pure extraction and exploitation similar to the chaos companies like Facebook and Amazon leave in their wake, and despite a persistent anxiety that they be “good” for something, or have some sort of vaguely-defined “culture,” they have also internalized the cheap thrills of late capitalism. Play an acclaimed, mature, long-awaited, whatever videogame, and you’re likely to come away with the impression that the only human emotions that matter are frustration, domination, horny and tfw number goes up, with maybe something about sparkling orbs or (mortal kombat announcer voice) emotional beat if it’s an especially artsy production. So few videogames are actually about something as common as visual pleasure, except in the shallow way of being graphically “breathtaking” in a comfortably boring, not-even-kitsch way. And yet, like hotels, they must all be reviewed…

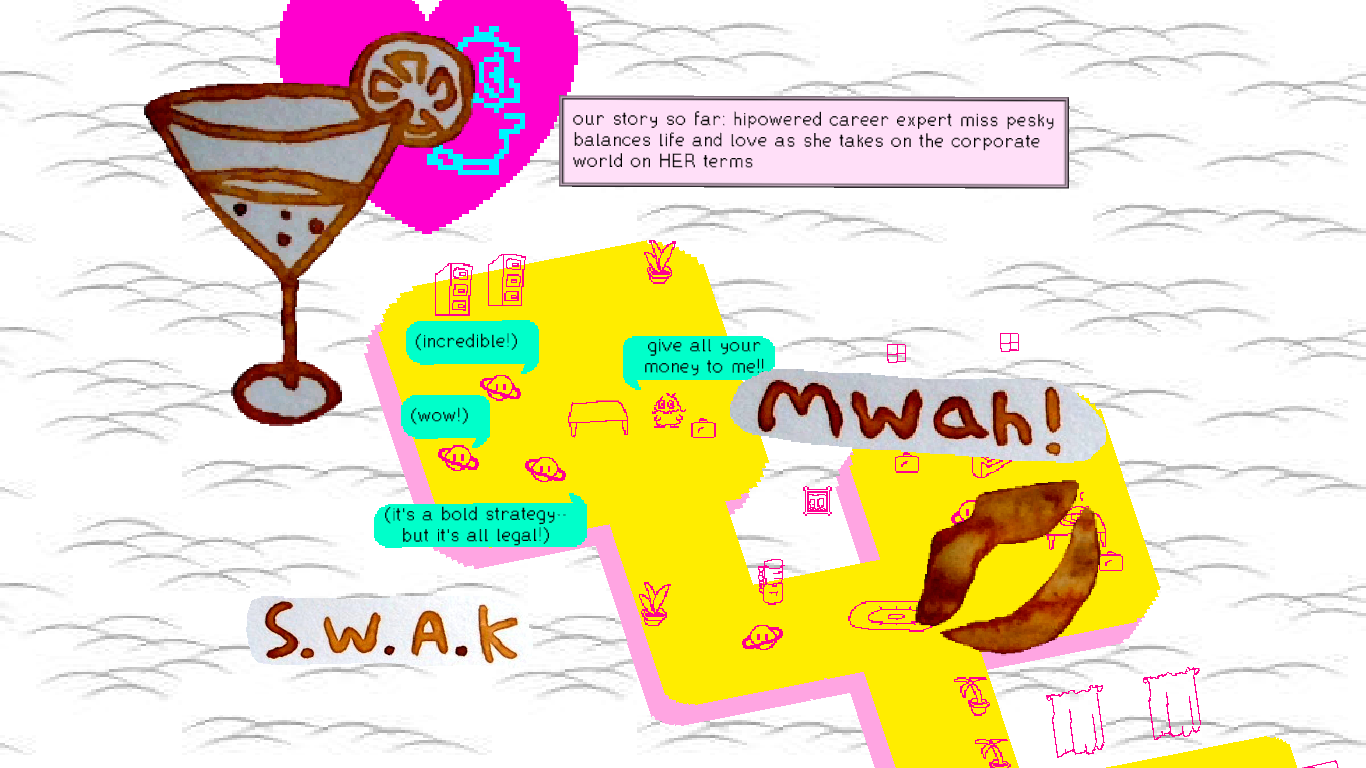

The player character, Pesky, is the indefatigable surge of performatively enthusiastic freelance, contract, precarious and aspirational hustle-style work as a collective which has become an increasingly vital portion of “flexible” “friendly” neoliberal capitalism (especially in the indie and games writing space). She’s swept up in the glamour of hotels, swanky corporate non-places, and eager to take on a role of uncertain stability or renumeration as various obscure movements of financialization happen around her, within the same hotels. But she has a certain malign quality as well. “Pesky;” her very nature could be as much impediment as boon to the grifting Mr Hotels and Mr Hostels of the world.

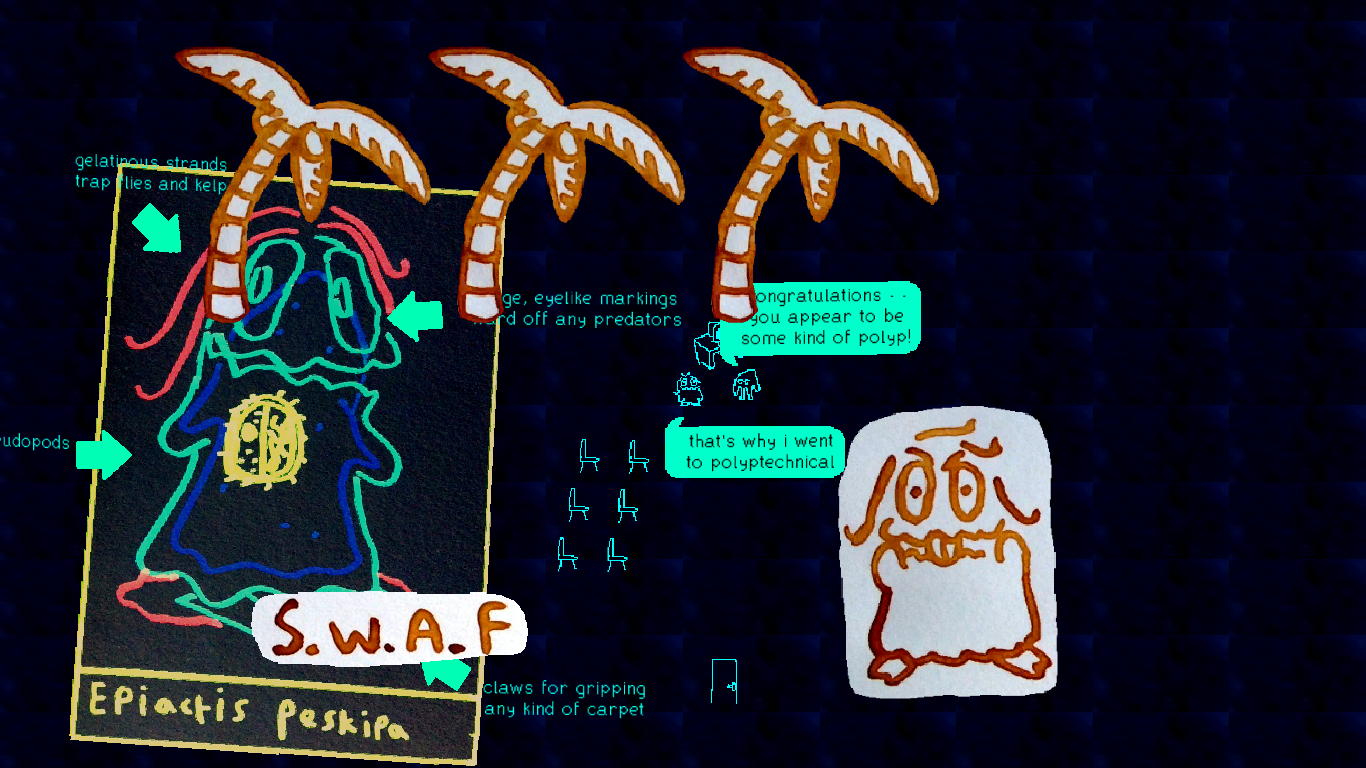

What is her nature? Her external appearance as a fairly unified and humanoid being is a façade concealing a polyp-like structure. When you take a screenshot, the increasingly common and formally facilitated way of commemorating and distributing gameplay moments in social-mediaspace, she multiplies, obscures, getting between the implied camera/eye and its object of interest. You get the feeling that her life cycle may be similar to that of Junji Ito’s Tomie, that if you cut her up into a million pieces and scattered them to the four winds, you’d only have that many Peskies to deal with within a short time.

While Mr Hotel ends her contract and shuts her out of the glamorously chaotic world of hotels for a time, it seems almost inevitable that she or something similar will push its way back in again. After all, the forces of capitalism inevitably have to come into icky sticky contact with this unpredictable mass – of “tricksters... spammers… artists… Temporary workers, students, teenagers, kids, other motley crowds of people” as Hito Steyerl describes the crowds at Les Misérables’ barricades. This is simultaneously the base of platform capitalism’s throne and the sword of Damocles hovering over its head. While Pesky is primarily an observer of all the dysfunctional economies contained within the hotel, those witnessing her misadventures understand that financial markets, rather than emerging from a natural or rational order (as the discipline of economics has emerged almost entirely for the purposes of arguing), are highly contingent, and thus subject to rejection and overthrow like anything else.

When Pesky bubbles up between the player’s eye and the screenshot image, she mischievously sabotages in some small way what has become a ubiquitous feature in games which functions not just as straightforward documentation of how a game looks at any given moment, but an economic mechanism for players to pick out the most appealing moments or sights in the gameplay and share them over social media as a sort of marketing, rather than the developers themselves having to curate the visual content of increasingly huge but modular “open worlds.” 10 Beautiful Postcards is not just taking bits of the flatgame ethos, which is, in the words of The Isle Is Full of Noises and Curtain’s dev, Dreamfeel, “about presenting a game as the most raw combination of movement, art and sound,” though the general lack of collision and collagey flatness of the areas make it arguably a flatgame. The game also self-consciously trips up any elements beyond collecting a set number of postcards to access the final scenes that would typically qualify it as a videogame. Most “interactivity” or “choices” within the areas are ironic or reversible. The concept of “difficulty” is not merely avoided but met with open hostility.

So the second thing I feel 10 Beautiful Postcards is doing is this essential removal of everything in a videogame except that which the snippet from Brendan Keogh’s paper at the top of this post would call: “the embodied perception of digital sights and sounds,” the audio-visual-haptics. There are many games which obviously expect to be admired on the basis of their technical complexity, but they so rarely seem to be conscious of actually being looked at in the process beyond making sure the camera generally points in the direction you’re going and maybe showing off awareness of a few cinematic conventions to let you know you’re approaching a particularly cool part. 10 Beautiful Postcards, on the other hand, is always aware of the relationship between eye and screen, via the hands. Pesky is a sort of avatar/cursor/eye that indicates and follows your curiosity and interests; in some stages she literally becomes an eye. While it may seem like a step backwards for those who are still anxious about videogames’ value lying in how they can differentiate from other visual media, by taking away anything else the avatar/cursor/eye can do, 10 Beautiful Postcards asserts the importance of an alternate history of videogames, digital media, digital engagement, and the potential in throwing out all the rules.