Source: http://www.project1947.com/shg/symposium/p229shapes.html

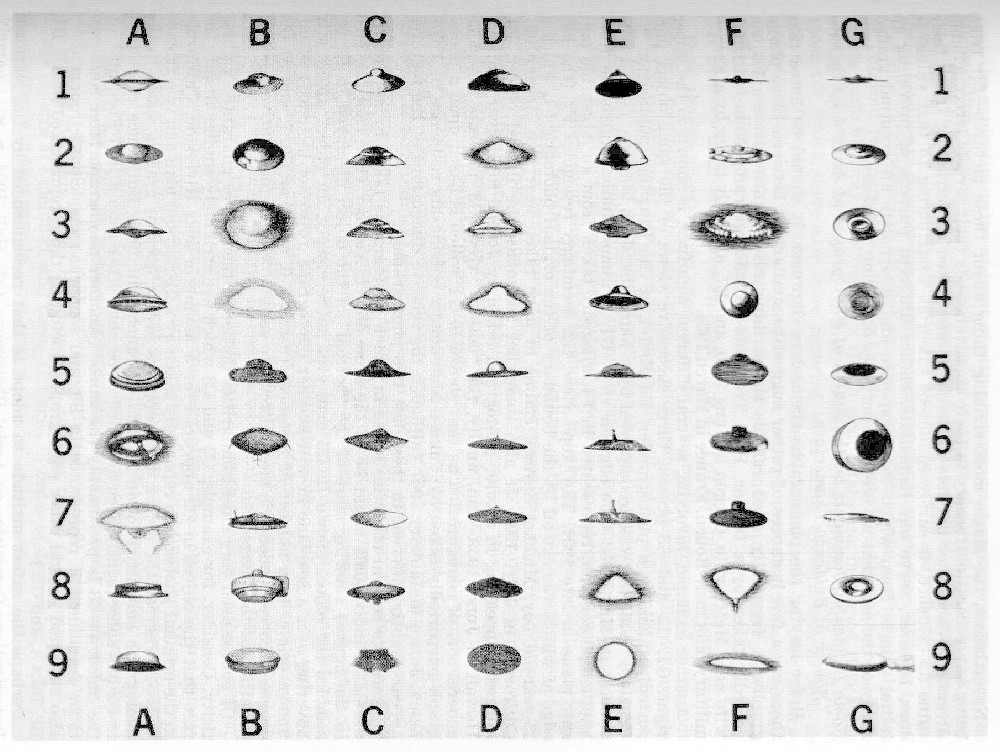

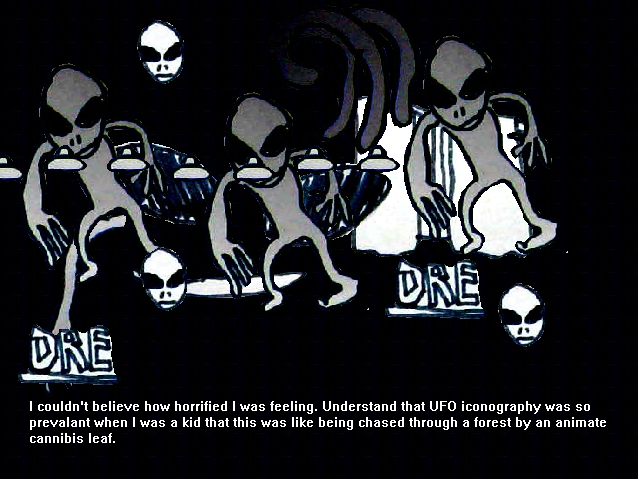

Real UFO Stories is a new zine I made at a videogame themed zine jam over the weekend. Basically I went through retro gaming magazines snipping out images of sprites I liked in hopes that a general theme would emerge. Some of the obvious and most appealing ones were UFOs, aliens, spacecraft in general. This worked well because I also really like the imagery of 1960s flying saucer identification charts.

Source: http://www.project1947.com/shg/symposium/p229shapes.html

The idea of classifying and sorting something that is, necessarily, unknown, apparently impervious to proper documentation and identification, is really intriguing. The categories are always shifting, new ones pop up to accommodate new phenomena. They represent the distinctions that are useful to us, as largely clueless observers, and may, ultimately, be meaningless.

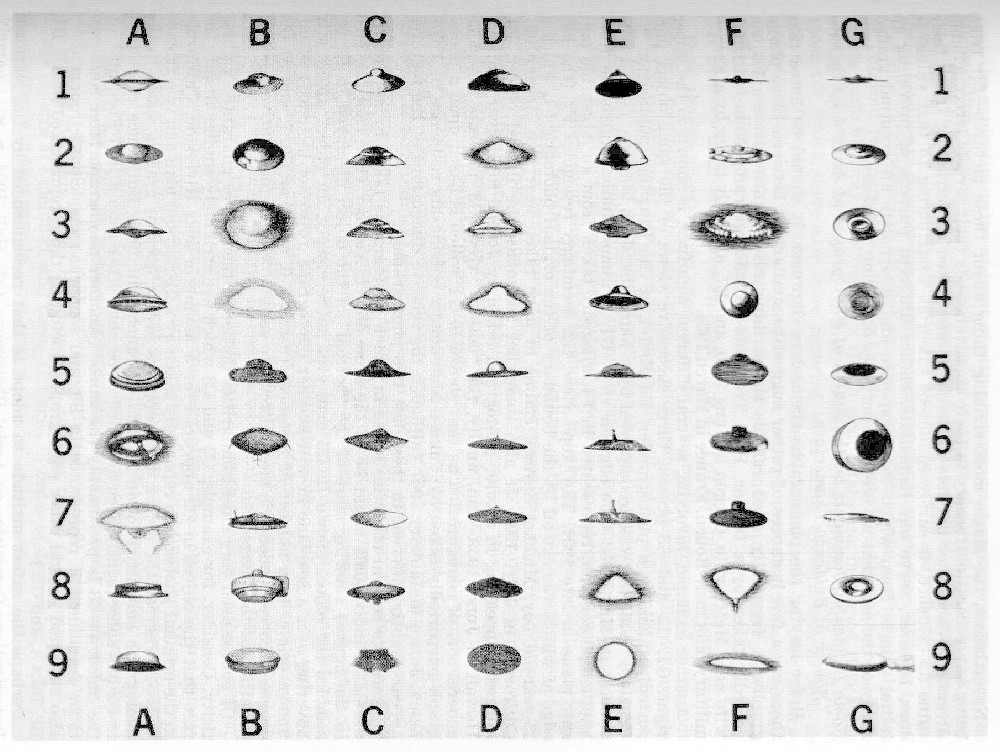

In high school I spent a lot of time in boring computer lab classes browsing the MUFON database because it was one of the few things I found entertaining that wasn’t blocked by the web filter. I even made a carefully-organized blog to save the text of my favorite reports. You can still do the same searches I did back then with the same basic interface I used. Most days I’d just browse the most recent, but sometimes it was more interesting to scroll through the long lists of attributes and categories and see if any iterations of my pick-and-choose encounter actually did exist.

Real UFO Stories comes from an interest in the relationship between typologies and the very human processes by which they emerge. It’s a back and forth of meaning-making, we notice “the differences that make a difference,” to us anyway, and then these differences shape how the knowledge coming after is formulated and understood. Of course, things can be sorted and organized in different ways and how we end up doing so determines how that collection is used and also, reflexively says a lot about why the things within it were collected.

Typologies are, in a way, the most basic form of information technology. They don’t necessarily have to be material tech in the way that a chart or filing cabinet is, but they are a man-made device that allows us to make sense of the unintelligible mass in ways that suit us. This is why I’m interested in typologies in my larger research work especially. Museums use typology to both collectivize and isolate special examples of objects, further, there are many types of museums and exhibitions and distinct impressions or overarching narratives can be pulled out of many placed side by side. When the types of things you’re analyzing are as deliberate as art exhibitions, for example, breaking them into typologies can be useful because their familiarity and institutional established-ness can make how their “types” function invisible, effectively naturalized. We aren’t really meant to see exhibition styles, but the work on display, with few exceptions.

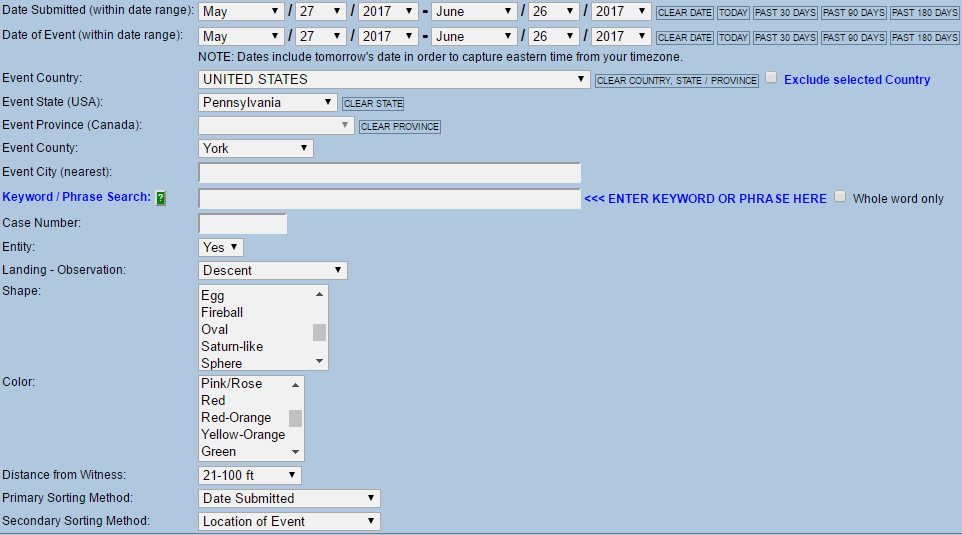

Something like UFO sightings is a much less institutionalized, more marginal cultural form. This is perhaps why something like TV Tropes flourishes analyzing the cheap, disposable, and formulaic in TV, videogames, comics and so on, while there’s not really as popular an equivalent for classical oil painting or modern dance. UFO sightings both are formed by and form our especially pulpy sci-fi imagination. Direct encounters with UFOs, both in fiction and in real life are almost always saturated with intense emotions, unexplainable curiosity against your usual better judgement, paralyzing fear, lingering paranoia and trauma, and alternately, equally inexplicable feelings of peace or bliss. These intense experiences are screened through the melodrama and camp of sci-fi and become a dispersed trace, in circulated blurry photos that translate to colorful blocky sprites and stylized cabinet art revived years later as retro game signifiers.

When I had made the typology that structures the zine I got kind of stumped on how to fill them. I didn’t really have any sort of inspiration to write my own fiction definitions, (though Field Guys and Apple Quest Monsters are two recent zines that do this and are absolutely lovely) and while I had always loved digging in and reading the MUFON archives, just lifting quotes from cases didn't seem transformative enough. The weird blurry unnaturalness yet underlying coherence of predictive text was where I landed.

The text in the zine is, importantly, not generative text and I think it’s important to be clear about how it was made and what that means. Generative text would be the program composing on its own given a sufficient set of examples or a framework and vocabulary to fit together, instead I’m using what is often described as generative text but is more of a collaboration between software, corpus and writer, a predictive text interface. For more of the technical nitty gritty on how it works, you can look at the git repository of pt-voicebox, but I’ll explain here how it feels to use.

It’s a bit like a verbal game of exquisite corpse opposite a COM opponent. I create a large text document which is a selection of several sighting reports that contain the keyword in that instance of the typology, ie “saucer.” The program reads this document and using word counting and probability and so on proposes a list of words that it thinks are most appropriate to use next. I select, and it repeats the process, in relation to the selected word. It’s kind of like playing the back and forth game of where you want to eat for dinner, one person provides a list of foods, the other picks, then it’s narrowed to a selection of places you can go, and you reach some kind of collaborative outcome. It’s composition within certain constraints, which is, I guess, a broad way of describing poetry in general.

This sort of predictive text interface is another site where now computers are increasingly looking at us, or listening to what we put down, and trying to understand us. I feel like these are real UFO stories in that they are made of a collaboration between humans, both the people who wrote the original reports and my limited syntax within the predictive text interface, and a digital interface trying to understand the stories within these reports (“true (or real) stories” subjectively oscillating between oxymoron and tautology never quite reaching either). They are not strictly real in that they are a firsthand account of something that was seen, (even then some people would say that is not “real” enough because UFOs themselves are not sufficiently “real”), but they are real in the way that types emerge as real, structuring and guiding our understanding and choices resulting from what happens to us.

In the resulting texts I think the “types” shone through, for one thing, the text was not made completely random or nonsensical from the mediation. I also think they surprisingly retained the powerful and ambivalent emotional sum that make online UFO reporting databases so beguiling in the first place.